Liz Stewart and Anna Johnson contributed to this story.

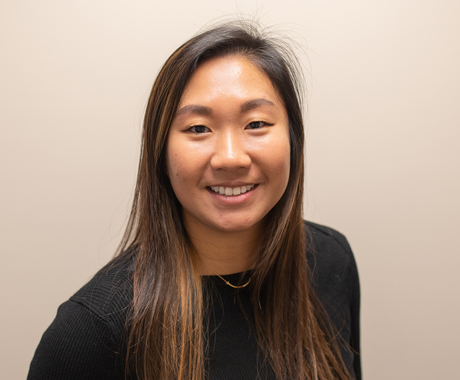

Yvette Arellano is an example of how lived experience and perspective in one’s work can increase its impact.

Prior to founding Fenceline Watch, Yvette was a dedicated environmental justice advocate for several years.

From door-knocking, to spreading the word about state agency meetings regarding potential increases in emissions from regional manufacturing plants, to testifying before Congress, Yvette saw glaring issues keeping the community from participating.

“Community members would be given a short window to respond. All of the available information and statement by the polluting facilities and state agencies would be in English, and the agencies had no one to translate for them,” shared Yvette.

Yvette is a first-generation American born and raised in Houston; their parents immigrated from Mexico. Houston is widely considered the energy capital of the world and home to a 52-mile stretch of oil, gas and petrochemical infrastructure along the Houston Ship Channel. They have the lived experience of the environmental, safety, and health harms their community is forced to absorb from the oil, gas and petrochemical industry.

They decided to bring this perspective into their work directly, and founded the organization Fenceline Watch. The organization is committed to fighting the toxic multi-generational harm faced by communities living at the fenceline of fossil fuel industries.

“Since I was little, I was translating for my mom at doctors' visits, and with utility companies, language barriers are a known barrier for my community… for years I translated state documents about upcoming polluting projects to try and get others out to public hearings. They would come, and then the meetings would be in very technical language and only in English, and they would leave.”

Yvette began the process of gathering information and setting the foundation for a Civil Rights Complaint, and received an unprecedented 48-hour turnaround from the Department of Justice. The changes at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and corresponding outcomes for communities throughout the state included:

- A change to the rules to provide adequate translation and interpretation services.

- Provide a protected 30 days notice for communities regarding air, water and waste permits for all Texas communities.

- Provide Plain Language Summaries of permit applications for all Texas communities.

- Begin the process for a Public Participation Plan & Language Access Plan.

They then focused on protecting the public input process, organizing support from 29 national, state, and regional environmental and community organizations to decrease language barriers in other formal input processes. One result: a delay of the GulfLink Terminal that would transport 2 million barrels of crude oil a day.

The U.S. Coast Guard extended their comment period for the GulfLink Terminal to ensure Spanish-speaking communities had a chance to offer input.

Because of Yvette’s passion for protecting the environment and helping others in the process, they were chosen to receive the 2023 Environmental Leader Award, an independent project administratively supported by the Center for Rural Affairs and made possible by the Walton Family Foundation.

This award honors accomplished leaders in the field of environmental stewardship and recognizes individuals with a proven track record and promise of future advancement in the field.

Local advocacy has national impact

Houston, where Fenceline Watch is based, is home to the largest petrochemical manufacturing complex in the nation, with 618 chemical facilities. Pollution from this sector has profound impacts on people living near the plants, as well as on downstream ecosystems and surrounding fisheries.

Fenceline Watch is leading efforts to help the city's most underserved populations work against the petrochemical expansion fueled by plastics production. Plastics pollution has multi-generational effects on people through a process called “bioaccumulation,” where toxic chemicals slowly build up in a body over time after repeated exposure.

“We’re not just talking about asthma or cancer; we’re talking about long-lasting toxic impacts,” Yvette said. “Fenceline Watch is dedicated to helping frontline communities.”

“Everyone should know how public processes run,” Yvette said. “Seeing little kids being the translators, having to take time to explain how they were being affected, and the parents trying to use words small enough for their children to speak, made me wonder why anyone would put a child in that position. It felt very cold, and the fact that those running the meetings didn’t stop voluntarily and notice was not okay.”

They started to identify pathways where the environmental agencies could be pressured to listen to community members.

These changes offer communities equitable access to public input processes and opportunity to officially voice concerns about the ongoing effects of pollution, plus the commission now accepts environmental complaints in languages other than English.

Yvette noted their community is often downwind from the petrochemical plants, and residents experience strong chemical odors and exposure in their homes. Having equal access to file environmental complaints provides the ability of the community to create a public record of the harm they are experiencing.

Houston is not the only community to experience these benefits. Other agencies that have changed the accessibility of their public comment processes include the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management.

Local efforts, global community

Yvette and their colleagues at Fenceline Watch understand advocating against the effects of petrochemical pollution must include a systemic change in which historical barriers, including language, are removed.

In 2023, Fenceline Watch received an accreditation that allows it to observe and submit comments in the United Nations Environment Assembly. That same year, Yvette spoke at the global plastics treaty negotiations in Paris.

Yvette also serves as a co-chair for the Backbone Campaign, is a board member for both the Center for International Environmental Law and GreenLatinos, and is the secretary of Super Neighborhood 65 & 82 in Houston.

In all their work, Yvette stresses that access to clean water, air, land, and food is a fundamental human right.